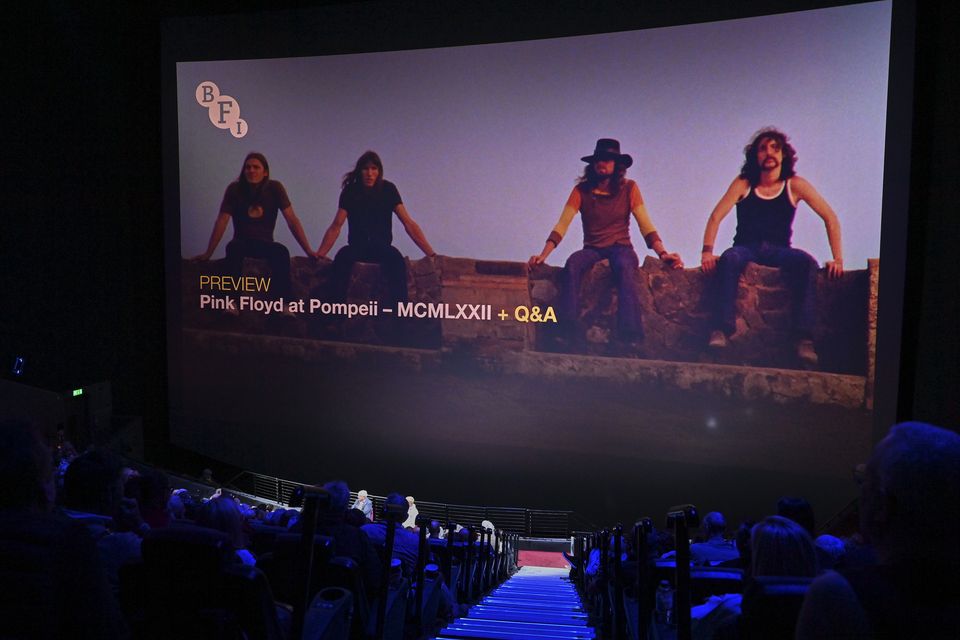

Pink Floyd at Pompeii − MCMLXXII: Slightly pretentious 1972 art movie has been restored – and should be required viewing

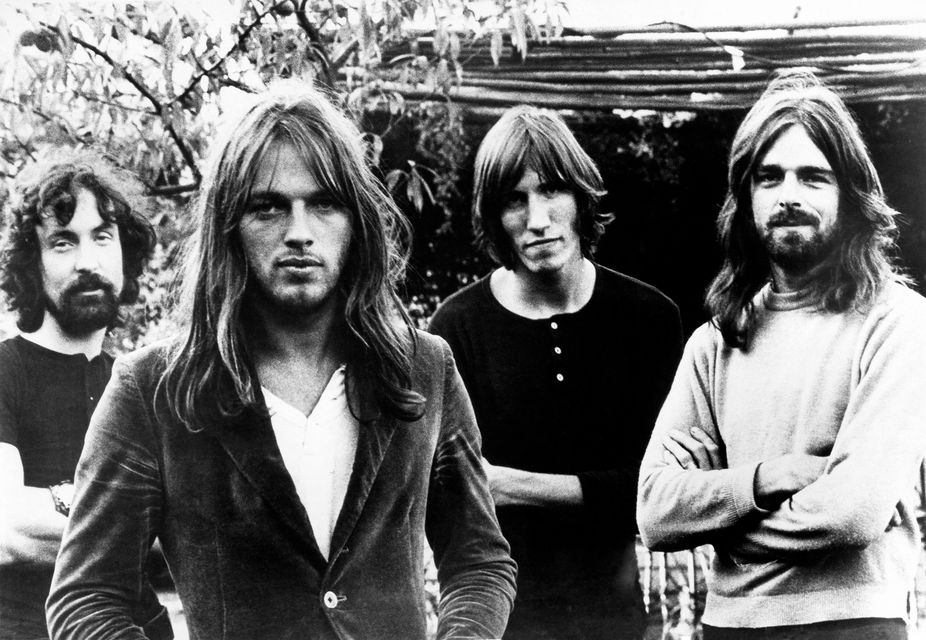

Viewers can see the band in their heyday in the "Pink Floyd at Pompeii - MCMLXXII" film. Photo: Getty Images

“Some people think we are a relic of the past,” admits Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason, staring into the cameras. Mason is all of 28 years old, in the prime of youth and vigour, but actually does look like a relic.

His huge mound of long curly hair and proud handlebar moustache date the film almost as much as the incessant smoking of keyboard player Rick Wright.

The year is 1972, commemorated by the Roman numerals MCMLXXII for this lovingly restored concert documentary Pink Floyd at Pompeii. The rock quartet are at the apex of their psychedelic phase but have yet to go globally imperial with the release the following year of Dark Side of the Moon − of which the film offers tantalising glances.

Director Adrian Maben came up with the unusual idea of having the band perform their interstellar rock to the empty crumbling Pompeii amphitheatre with no audience but a shirtless film crew baking in the relentless sun.

It was viewed as a slightly pretentious art movie, an impression compounded by shots of the band walking around Mount Vesuvius’ slopes and staring into bubbling pools of lava whilst David Gilmour’s distorted slide guitar echo around the stark volcanic landscape. Fifty-three years on it looks utterly magnificent, a glorious record of a group at the height of their powers that will delight every old rocker and should be required viewing for aspiring young musicians.

Pinl Floyd's Nick Mason, David Gilmour, Roger Waters and Rick Wright in 1973. Photo: Getty

Through a lens of hindsight, the setting suggests not so much antiquity as timelessness and classicism, implying Pink Floyd deserve to be viewed outside of rock history as part of a much greater span of creation.

Floyd themselves look shockingly young, as a shirtless, long-haired Gilmour fiddles with his effects unit and produces sounds from his instrument that shift across a dazzling spectrum, from ethereal weirdness to delicate melodiousness and grinding attack.

His future nemesis Roger Waters wears a slim black vest and grips his bass guitar with taut, muscular arms, picking out mobile and at times almost funky grooves amidst tumbling expanses of sound. The future curmudgeon certainly looks like he’s enjoying himself.

Rick Wright smokes quietly in the background and effortlessly conjures warm vistas of piano, organ and synthesiser that float between all the spaces in the songs. When he joins Gilmour in tight vocal harmony on Echoes, you really hear the gorgeous signature sound of Pink Floyd.

The equipment isn’t thinking about what to do

The star of the film, though, is not the Adonis-like Gilmour, and certainly not the enthusiastically gurning Waters. It is Nick Mason, arms flying around his drum kit in incessant action, head swivelling to connect with his band members, his jazzy, groovy, loose but sensually-felt playing at the centre of everything, holding the band’s flights of fancy together. The man certainly loves his cymbals, which shimmer and tingle even in the quietest moments.

It struck me how little you hear cymbals in modern music, relegated to a percussive effect by the metronomic logic of drum machines and digital programming. The flamboyantly experimental Saucerful of Secrets remains utterly astonishing, all the more so when you see these four young men conjuring it out of nothing.

Discussing their “reliance” on technology, Gilmour stares into the camera with amused disdain. “The equipment isn’t thinking about what to do. It couldn’t control itself,” he says.

Now music is entering an era when the equipment can control itself, when AI threatens to eradicate all human invention and spontaneity from musical creation. This amazing movie shows us what the cost of that might be, because a group like Pink Floyd would find it hard to exist and certainly could not thrive in this reductive, generic streaming age.

What would rock’n’roll be without feedback?

The volcanic action is interspersed with scenes filmed in Abbey Road during the recording of Dark Side of the Moon, which offer extraordinary glimpses of glories to come, particularly Waters fiddling with a now-vintage synthesiser until the burbling sequence of On the Run miraculously emerges, with Waters glancing up to ask if someone is getting this.

Wright sits in a cloud of blue cigarette smoke, fingers floating across piano keys like a jazz maestro on Us and Them.

These scenes were apparently staged rather than representing the actual recording sessions, yet they nevertheless afford intriguing insights into fractures that will ultimately destroy this band.

Playing a solo to Brain Damage, Gilmour pulls a sour face when Waters continually interrupts from control room, complaining about feedback. “Don’t worry about that,” grumbles Gilmour. “What would rock’n’roll be without feedback?”

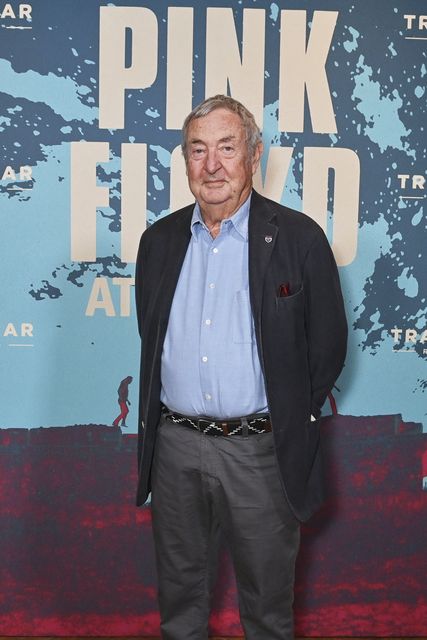

Nick Mason at the screening (Dave Bennet)

“We have some pretty good arguments from time to time,” Gilmour admits, oblivious to the bitterness and acrimony that lies ahead. He and Mason were present at the film’s premiere at the BFI Imax London and could be seen laughing at their younger selves.

At 79, Gilmour has the craggy stolidity of the Vesuvian landscape. At 81, Mason looks less like a rock star than a retired investment banker. But both are still making exciting music and still going about it with an old-fashioned dedication to technical craft.

Wright has been dead for almost seven years. The absent Waters, meanwhile, soldiers on as a controversial touring superstar, reshaping Pink Floyd’s legacy from the later sequences of albums dominated by his song-writing, while indulging a nasty public feud with Gilmour.

It doesn’t quite match the fly-on-the-wall intimacy of The Beatles’s Get Back documentary series but it is glorious to see and hear this incredible band in their youthful prime.

Pink Floyd at Pompeii − MCMLXXII will be released in select cinemas and Imax worldwide from April 24. The live album will be released for the first time in a new remix by Steven Wilson from May 2 in all formats

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news