Two of the most monstrous regimes in human history came to power in the 20th century, and both were predicated on the violation and despoiling of truth, on the knowledge that cynicism and weariness and fear can make people susceptible to the lies and false promises of leaders bent on unconditional power. As Hannah Arendt wrote in her 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (ie the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (ie the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

Arendt’s words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a chilling description of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today – a world in which fake news and lies are pumped out in industrial volume by Russian troll factories, emitted in an endless stream from the mouth and Twitter feed of the president of the United States, and sent flying across the world through social media accounts at lightning speed. Nationalism, tribalism, dislocation, fear of social change and the hatred of outsiders are on the rise again as people, locked in their partisan silos and filter bubbles, are losing a sense of shared reality and the ability to communicate across social and sectarian lines.

This is not to draw a direct analogy between today’s circumstances and the overwhelming horrors of the second world war era, but to look at some of the conditions and attitudes – what Margaret Atwood has called the “danger flags” in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm – that make a people susceptible to demagoguery and political manipulation, and nations easy prey for would-be autocrats. To examine how a disregard for facts, the displacement of reason by emotion, and the corrosion of language are diminishing the value of truth, and what that means for the world.

The term “truth decay” has joined the post-truth lexicon that includes such now familiar phrases as “fake news” and “alternative facts”. And it’s not just fake news either: it’s also fake science (manufactured by climate change deniers and anti-vaxxers, who oppose vaccination), fake history (promoted by Holocaust revisionists and white supremacists), fake Americans on Facebook (created by Russian trolls), and fake followers and “likes” on social media (generated by bots).

Donald Trump, the 45th president of the US, lies so prolifically and with such velocity that the Washington Post calculated he’d made 2,140 false or misleading claims during his first year in office – an average of 5.9 a day. His lies – about everything from the investigations into Russian interference in the election, to his popularity and achievements, to how much TV he watches – are only the brightest blinking red light among many warnings of his assault on democratic institutions and norms. He routinely assails the press, the justice system, the intelligence agencies, the electoral system and the civil servants who make the US government tick.

Nor is the assault on truth confined to America. Around the world, waves of populism and fundamentalism are elevating appeals to fear and anger over reasoned debate, eroding democratic institutions, and replacing expertise with the wisdom of the crowd. False claims about the UK’s financial relationship with the EU helped swing the vote in favour of Brexit, and Russia ramped up its sowing of dezinformatsiya in the runup to elections in France, Germany, the Netherlands and other countries in concerted propaganda efforts to discredit and destabilise democracies.

How did this happen? How did truth and reason become such endangered species, and what does the threat to them portend for our public discourse and the future of our politics and governance?

It’s easy enough to see Trump as having ascended to office because of a unique, unrepeatable set of factors: a frustrated electorate still hurting from the backwash of the 2008 financial crash; Russian interference in the election and a deluge of pro-Trump fake news stories on social media; a highly polarising opponent who came to symbolise the Washington elite that populists decried; and an estimated $5bn‑worth of free campaign coverage from media outlets obsessed with the views and clicks that the former reality TV star generated.

If a novelist had concocted a villain like Trump – a larger-than-life, over-the-top avatar of narcissism, mendacity, ignorance, prejudice, boorishness, demagoguery and tyrannical impulses (not to mention someone who consumes as many as a dozen Diet Cokes a day) – she or he would likely be accused of extreme contrivance and implausibility. In fact, the president of the US often seems less like a persuasive character than some manic cartoon artist’s mashup of Ubu Roi, Triumph the Insult Comic Dog, and a character discarded by Molière. But the more clownish aspects of Trump the personality should not blind us to the monumentally serious consequences of his assault on truth and the rule of law, and the vulnerabilities he has exposed in our institutions and digital communications. It is unlikely that a candidate who had already been exposed during the campaign for his history of lying and deceptive business practices would have gained such popular support were portions of the public not blase about truth-telling and were there not systemic problems with how people get their information and how they’ve come to think in increasingly partisan terms.

With Trump, the personal is political, and in many respects he is less a comic-book anomaly than an extreme, bizarro-world apotheosis of many of the broader, intertwined attitudes undermining truth today, from the merging of news and politics with entertainment, to the toxic polarisation that’s overtaken American politics, to the growing populist contempt for expertise.

For decades now, objectivity – or even the idea that people can aspire toward ascertaining the best available truth – has been falling out of favour. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s well-known observation that “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts” is more timely than ever: polarisation has grown so extreme that voters have a hard time even agreeing on the same facts. This has been exponentially accelerated by social media, which connects users with like-minded members and supplies them with customised news feeds that reinforce their preconceptions, allowing them to live in ever narrower silos.

For that matter, relativism has been ascendant since the culture wars began in the 1960s. Back then, it was embraced by the New Left, who were eager to expose the biases of western, bourgeois, male-dominated thinking; and by academics promoting the gospel of postmodernism, which argued that there are no universal truths, only smaller personal truths – perceptions shaped by the cultural and social forces of one’s day. Since then, relativistic arguments have been hijacked by the populist right.

Relativism, of course, synced perfectly with the narcissism and subjectivity that had been on the rise, from Tom Wolfe’s “Me Decade” 1970s, on through the selfie age of self-esteem. No surprise then that the “Rashomon effect” – the point of view that everything depends on your point of view – has permeated our culture, from popular novels such as Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies to television series like The Affair, which hinge on the idea of competing realities.

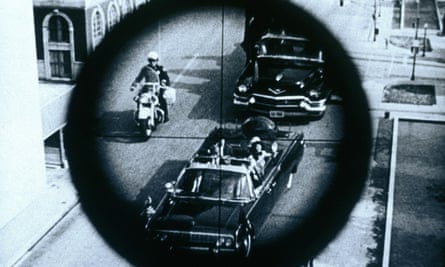

I’ve been reading and writing about many of these issues for nearly four decades, going back to the rise of deconstruction and battles over the literary canon on college campuses; debates over the fictionalised retelling of history in movies such as Oliver Stone’s JFK and Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty; efforts made by both the Clinton and Bush administrations to avoid transparency and define reality on their own terms; Trump’s war on language and efforts to normalise the abnormal; and the impact that technology has had on how we process and share information.

In his 2007 book, The Cult of the Amateur, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur Andrew Keen warned that the internet not only had democratised information beyond people’s wildest imaginings but also was replacing genuine knowledge with “the wisdom of the crowd”, dangerously blurring the lines between fact and opinion, informed argument and blustering speculation. A decade later, the scholar Tom Nichols wrote in The Death of Expertise that a wilful hostility towards established knowledge had emerged on both the right and the left, with people aggressively arguing that “every opinion on any matter is as good as every other”. Ignorance was now fashionable.

The postmodernist argument that all truths are partial (and a function of one’s perspective) led to the related argument that there are many legitimate ways to understand or represent an event. This both encouraged a more egalitarian discourse and made it possible for the voices of the previously disfranchised to be heard. But it has also been exploited by those who want to make the case for offensive or debunked theories, or who want to equate things that cannot be equated. Creationists, for instance, called for teaching “intelligent design” alongside evolution in schools. “Teach both,” some argued. Others said, “Teach the controversy.”

A variation on this “both sides” argument was employed by Trump when he tried to equate people demonstrating against white supremacy with the neo-Nazis who had converged in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of Confederate statues. There were “some very fine people on both sides”, Trump declared. He also said, “We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides, on many sides.”

Climate deniers, anti-vaxxers and other groups who don’t have science on their side bandy about phrases that wouldn’t be out of place in a college class on deconstruction – phrases such as “many sides,” “different perspectives”, “uncertainties”, “multiple ways of knowing.” As Naomi Oreskes and Erik M Conway demonstrated in their 2010 book Merchants of Doubt, rightwing thinktanks, the fossil fuel industry, and other corporate interests that are intent on discrediting science have employed a strategy first used by the tobacco industry to try to confuse the public about the dangers of smoking. “Doubt is our product,” read an infamous memo written by a tobacco industry executive in 1969, “since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the minds of the general public.”

The strategy, essentially, was this: dig up a handful of so-called professionals to refute established science or argue that more research is needed; turn these false arguments into talking points and repeat them over and over; and assail the reputations of the genuine scientists on the other side. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a tactic that’s been used by Trump and his Republican allies to defend policies (on matters ranging from gun control to building a border wall) that run counter to both expert evaluation and national polls.

What Oreskes and Conway call the “tobacco strategy” was helped, they argued, by elements in the mainstream media that tended “to give minority views more credence than they deserve”. This false equivalence was the result of journalists confusing balance with truth-telling, wilful neutrality with accuracy; caving in to pressure from rightwing interest groups to present “both sides”; and the format of television news shows that feature debates between opposing viewpoints – even when one side represents an overwhelming consensus and the other is an almost complete outlier in the scientific community. For instance, a 2011 BBC Trust report found that the broadcaster’s science coverage paid “undue attention to marginal opinion” on the subject of manmade climate change. Or, as a headline in the Telegraph put it, “BBC staff told to stop inviting cranks on to science programmes”.

In a speech on press freedom, CNN’s chief international correspondent Christiane Amanpour addressed this issue in the context of media coverage of the 2016 presidential race, saying: “It appeared much of the media got itself into knots trying to differentiate between balance, objectivity, neutrality, and crucially, truth … I learned long ago, covering the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Bosnia, never to equate victim with aggressor, never to create a false moral or factual equivalence, because then you are an accomplice to the most unspeakable crimes and consequences. I believe in being truthful, not neutral. And I believe we must stop banalising the truth.”

As the west lurched through the cultural upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s and their aftermath, artists struggled with how to depict this fragmenting reality. Some writers like John Barth, Donald Barthelme and William Gass created self-conscious, postmodernist fictions that put more emphasis on form and language than on conventional storytelling. Others adopted a minimalistic approach, writing pared-down, narrowly focused stories emulating the fierce concision of Raymond Carver. And as the pursuit of broader truths became more and more unfashionable in academia, and as daily life came to feel increasingly unmoored, some writers chose to focus on the smallest, most personal truths: they wrote about themselves.

American reality had become so confounding, Philip Roth wrote in a 1961 essay, that it felt like “a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination”. This had resulted, he wrote, in the “voluntary withdrawal of interest by the writer of fiction from some of the grander social and political phenomena of our times”, and the retreat, in his own case, to the more knowable world of the self.

In a controversial 1989 essay, Tom Wolfe lamented these developments, mourning what he saw as the demise of old-fashioned realism in American fiction, and he urged novelists to “head out into this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, hog-stomping Baroque country of ours and reclaim it as literary property”. He tried this himself in novels such as The Bonfire of the Vanities and A Man in Full, using his skills as a reporter to help flesh out a spectrum of subcultures with Balzacian detail. But while Wolfe had been an influential advocate in the 1970s of the New Journalism (which put an emphasis on the voice and point of view of the reporter), his new manifesto didn’t win many converts in the literary world. Instead, writers as disparate as Louise Erdrich, David Mitchell, Don DeLillo, Julian Barnes, Chuck Palahniuk, Gillian Flynn and Groff would play with devices (such as multiple points of view, unreliable narrators and intertwining storylines) pioneered decades ago by innovators such as William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Ford Madox Ford and Vladimir Nabokov to try to capture the new Rashomon-like reality in which subjectivity rules and, in the infamous words of former president Bill Clinton, truth “depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is”.

But what Roth called “the sheer fact of self, the vision of self as inviolable, powerful, and nervy, self as the only real thing in an unreal environment” would remain more comfortable territory for many writers. In fact, it would lead, at the turn of the millennium, to a remarkable flowering of memoir writing, including such classics as Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club and Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius – books that established their authors as among the foremost voices of their generation. The memoir boom and the popularity of blogging would eventually culminate in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume autobiographical novel, My Struggle – filled with minutely detailed descriptions, drawn from the author’s own daily life.

Personal testimony also became fashionable on college campuses, as the concept of objective truth fell out of favour and empirical evidence gathered by traditional research came to be regarded with suspicion. Academic writers began prefacing scholarly papers with disquisitions on their own “positioning” – their race, religion, gender, background, personal experiences that might inform or skew or ratify their analysis.

In a 2016 documentary titled HyperNormalisation, the filmmaker Adam Curtis created an expressionistic, montage-driven meditation on life in the post-truth era; the title was taken from a term coined by the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak to describe life in the final years of the Soviet Union, when people both understood the absurdity of the propaganda the government had been selling them for decades and had difficulty envisioning any alternative. In HyperNormalisation, which was released shortly before the 2016 US election, Curtis says in voiceover narration that people in the west had also stopped believing the stories politicians had been telling them for years, and Trump realised that “in the face of that, you could play with reality” and in the process “further undermine and weaken the old forms of power”.

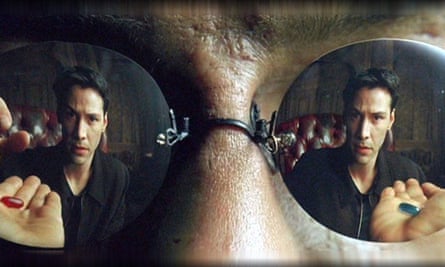

Some Trump allies on the far right also seek to redefine reality on their own terms. Invoking the iconography of the movie The Matrix – in which the hero is given a choice between two pills, a red one (representing knowledge and the harsh truths of reality) and a blue one (representing soporific illusion and denial) – members of the “alt-right” and some aggrieved men’s rights groups talk about “red-pilling the normies”, which means converting people to their cause. In other words, selling their inside-out alternative reality, in which white people are suffering from persecution, multiculturalism poses a grave threat and men have been oppressed by women.

Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis, the authors of a study on online disinformation, argue that “once groups have been red-pilled on one issue, they’re likely to be open to other extremist ideas. Online cultures that used to be relatively nonpolitical are beginning to seethe with racially charged anger. Some sci-fi, fandom, and gaming communities – having accepted run-of-the-mill antifeminism – are beginning to espouse white-nationalist ideas. ‘Ironic’ Nazi iconography and hateful epithets are becoming serious expressions of antisemitism.”

One of the tactics used by the alt-right to spread its ideas online, Marwick and Lewis argue, is to initially dilute more extreme views as gateway ideas to court a wider audience; among some groups of young men, they write, “it’s a surprisingly short leap from rejecting political correctness to blaming women, immigrants, or Muslims for their problems.”

Many misogynist and white supremacist memes, in addition to a lot of fake news, originate or gain initial momentum on sites such as 4chan and Reddit – before accumulating enough buzz to make the leap to Facebook and Twitter, where they can attract more mainstream attention. Renee DiResta, who studies conspiracy theories on the web, argues that Reddit can be a useful testing ground for bad actors – including foreign governments such as Russia’s – to try out memes or fake stories to see how much traction they get. DiResta warned in the spring of 2016 that the algorithms of social networks – which give people news that is popular and trending, rather than accurate or important – are helping to promote conspiracy theories.

This sort of fringe content can both affect how people think and seep into public policy debates on matters such as vaccines, zoning laws and water fluoridation. Part of the problem is an “asymmetry of passion” on social media: while most people won’t devote hours to writing posts that reinforce the obvious, DiResta says, “passionate truthers and extremists produce copious amounts of content in their commitment to ‘wake up the sheeple’”.

Recommendation engines, she adds, help connect conspiracy theorists with one another to the point that “we are long past merely partisan filter bubbles and well into the realm of siloed communities that experience their own reality and operate with their own facts”. At this point, she concludes, “the internet doesn’t just reflect reality any more; it shapes it”.

Language is to humans, the writer James Carroll once observed, what water is to fish: “We swim in language. We think in language. We live in language.” This is why Orwell wrote that “political chaos is connected with the decay of language”, divorcing words from meaning and opening up a chasm between a leader’s real and declared aims. This is why the US and the world feel so disoriented by the stream of lies issued by the Trump White House and the president’s use of language to disseminate distrust and discord. And this is why authoritarian regimes throughout history have co‑opted everyday language in an effort to control how people communicate – exactly the way the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four aims to deny the existence of external reality and safeguard Big Brother’s infallibility.

Orwell’s “Newspeak” is a fictional language, but it often mirrors and satirises the “wooden language” imposed by communist authorities in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe. Among the characteristics of “wooden language” that the French scholar Françoise Thom identified in a 1987 thesis were abstraction and the avoidance of the concrete; tautologies (“the theories of Marx are true because they are correct”); bad metaphors (“the fascist octopus has sung its swan song”); and Manichaeism that divides the world into things good and things evil (and nothing in between).

Trump has performed the disturbing Orwellian trick (“WAR IS PEACE”, “FREEDOM IS SLAVERY”, “IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH”) of using words to mean the exact opposite of what they really mean. It’s not just his taking the term “fake news”, turning it inside out, and using it to try to discredit journalism that he finds threatening or unflattering. He has also called the investigation into Russian election interference “the single greatest witch-hunt in American political history”, when he is the one who has repeatedly attacked the press, the justice department, the FBI, the intelligence services and any institution he regards as hostile.

In fact, Trump has the perverse habit of accusing opponents of the very sins he is guilty of himself: “Lyin’ Ted”, “Crooked Hillary”, “Crazy Bernie”. He accused Clinton of being “a bigot who sees people of colour only as votes, not as human beings worthy of a better future”, and he has asserted that “there was tremendous collusion on behalf of the Russians and the Democrats”.

In Orwell’s language of Newspeak, a word such as “blackwhite” has “two mutually contradictory meanings”: “Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this.”

This, too, has an unnerving echo in the behaviour of Trump White House officials and Republican members of Congress who lie on the president’s behalf and routinely make pronouncements that flout the evidence in front of people’s eyes. The administration, in fact, debuted with the White House press secretary, Sean Spicer, insisting that Trump’s inaugural crowds were the “largest audience” ever – an assertion that defied photographic evidence and was rated by the fact-checking blog PolitiFact a “Pants on Fire” lie. These sorts of lies, the journalist Masha Gessen has pointed out, are told for the same reason that Vladimir Putin lies: “to assert power over truth itself”.

Trump has continued his personal assault on the English language. His incoherence (his twisted syntax, his reversals, his insincerity, his bad faith and his inflammatory bombast) is emblematic of the chaos he creates and thrives on, as well as an essential instrument in his liar’s toolkit. His interviews, off‑teleprompter speeches and tweets are a startling jumble of insults, exclamations, boasts, digressions, non sequiturs, qualifications, exhortations and innuendos – a bully’s efforts to intimidate, gaslight, polarise and scapegoat.

Precise words, like facts, mean little to Trump, as interpreters, who struggle to translate his grammatical anarchy, can attest. Chuck Todd, the anchor of NBC’s Meet the Press, observed that after several of his appearances as a candidate Trump would lean back in his chair and ask the control booth to replay his segment on a monitor – without sound: “He wants to see what it all looked like. He will watch the whole thing on mute.”

Philip Roth said he could never have imagined that “the 21st-century catastrophe to befall the USA, the most debasing of disasters”, would appear in “the ominously ridiculous commedia dell’arte figure of the boastful buffoon”. Trump’s ridiculousness, his narcissistic ability to make everything about himself, the outrageousness of his lies, and the profundity of his ignorance can easily distract attention from the more lasting implications of his story: how easily Republicans in Congress enabled him, undermining the whole concept of checks and balances set in place by the founders; how a third of the country passively accepted his assaults on the constitution; how easily Russian disinformation took root in a culture where the teaching of history and civics had seriously atrophied.

The US’s founding generation spoke frequently of the “common good”. George Washington reminded citizens of their “common concerns” and “common interests” and the “common cause” they had all fought for in the revolution. And Thomas Jefferson spoke in his inaugural address of the young country uniting “in common efforts for the common good”. A common purpose and a shared sense of reality mattered because they bound the disparate states and regions together, and they remain essential for conducting a national conversation. Especially today in a country where Trump and Russian and hard-right trolls are working to incite the very factionalism Washington warned us about, trying to inflame divisions between people along racial, ethnic and religious lines.

There are no easy remedies, but it’s essential that citizens defy the cynicism and resignation that autocrats and power-hungry politicians depend on to subvert resistance. Without commonly agreed-on facts – not Republican facts and Democratic facts; not the alternative facts of today’s silo-world – there can be no rational debate over policies, no substantive means of evaluating candidates for political office, and no way to hold elected officials accountable to the people. Without truth, democracy is hobbled

- Michiko Kakutani’s The Death of Truth is published by William Collins on 26 July. To order a copy for £8.50 (RRP £10) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion