On the summer day in 2014 that June Provost found three stray cats dead and lined up side by side in his tractor, the forecast had called for rain. It was hot and overcast, the air like a heavy and suffocating blanket, and the sugarcane was already 6ft high.

Wenceslaus Provost Jr – who has gone by the name June since he can remember – stared in shock at the cats, each one with the tabby markings of strays. He could see no visible lacerations, no insides spilling out. He guessed it had been the work of a BB gun or a strangling.

He looked away, disgusted. As the breeze rattled through the sugarcane leaves, he thought: “This is a warning.”

A year earlier, June and his wife, Angie, had found a chain tied around the steering wheel of a tractor and the hydraulic lines stuffed with mud. But the dead cats were a marked escalation in intimidation. The following day, June found the windows of another tractor shot out. Later that season, someone hid cinderblocks in Angie’s fields to ruin the equipment.

Around that same time, Angie and June noticed vehicles parking near her fields, the drivers watching her work. June recognized one of the drivers as a representative of MA Patout & Son sugar mill, the company he contracted with to harvest and mill his sugarcane.

The whole season became an unrelenting act of apparent sabotage. Motor oil was repeatedly drained from vehicles. Fuel lines were filled with water. There was hardly a week without an incident.

“This was someone trying to stop the operation,” June says. “They knew exactly what to do with a tractor.”

After multiple police reports, June says, a sheriff’s deputy told them: “Someone wants what you have by any means necessary.”

In mid-May, the south Louisiana earth is parched, and the cane is nothing but 2ft-tall grass. Once the rain comes, it will grow like weeds. By August, the sugarcane will tower over grown men, and by late fall, it will be milled into molasses and raw sugar. During milling season, entire towns will smell like syrup. It’s a landscape reminiscent of the one shown in the television drama Queen Sugar – produced by the Oprah Winfrey Network and based on a novel by Natalie Baszile – about a black sugarcane farm family determined to save their land, despite blatant racism and land-grabbing by the white sugar mill owners.

Each year in Louisiana, farmers produce 13m tons of sugarcane, generating $3bn. It is a lucrative crop to produce, due to regulated production limits and tariff-rate quotas that protect US supply from foreign competition. It is, as the American Sugar Cane League proudly notes, “arguably the most successful crop in the history of our state”.

As a child, June, now 42, would prop his elbows in the windows of his dad’s baby blue Ford and they would ride out to check the cane fields, some of which have been farmed by his family for four generations. As a teenager, he filled diesel tanks and monitored oil levels in the tractors. At 18, he officially went to work on the family’s 2,500-acre farm. After his father retired in 2006, June began the process to purchase the business.

June Provost had the measurements of a successful farmer. He held nearly 4,500 acres and had been farming all his life. At 18, he won the state’s highest-yield contest– – 8,588lb of sugar per acre, 57% above the parish average. In 2008, the Louisiana Farm Bureau deemed him farmer of the year for Iberia parish.

But he says he endured years of discrimination in the form of coercive contracts, fraud, below-market crop loans, vandalism, and retaliation for speaking out about the mistreatment of black farmers – until he was finally forced out of business in 2015. “They took my livelihood, my family’s legacy,” says June, his voice swelling with grief. “They took what I love.”

June Provost’s exit from farming follows that of many black farmers in surrounding parishes. US census of agriculture statistics show a 44.7% decrease in black farm operators in Iberia parish – where the Provosts live – between 2007 and 2012, compared with a 12.3% decrease in white farm operators. In neighboring Vermillion parish, where June farmed the majority of his sugarcane, black farm operators decreased by 17% between 2002 and 2012, while white farmers increased by 6%. Nationally, less than 2% of farmers are black.

June says there were approximately 60 black sugarcane farmers in the area in 1983. He keeps their names neatly printed, line after line, in a notebook.

By 2000, that number had dwindled to 17. Today, June and Angie count only four.

On a humid May morning, the attorney Quinton Robinson rolls his briefcase toward a rental car in downtown Lafayette, Louisiana. He wears a crisp blue shirt, a striped bowtie, and a pair of wire-rimmed glasses on top of his head. The Provosts’ case, he says, “is one of day versus night, right versus wrong … with practices that can only be described as practices out of darkness”.

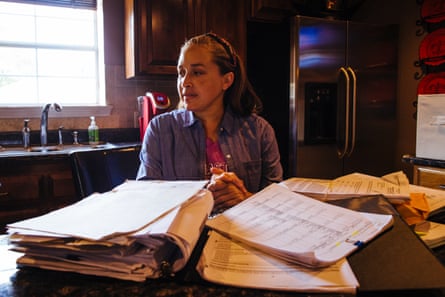

The family’s story is decades-long and mind-bending, accompanied by stacks of police reports, loan documents, foreclosure notices and legal petitions. The Provosts assert that white sugarcane farmers have been consistently offered more favorable loans and contracts by lenders and other agricultural entities than their black counterparts.

A lawsuit filed on 21 September by attorneys for the Provosts allege that First Guaranty Bank treated June differently than similarly situated white borrowers – violating on eight counts the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), the Fair Housing Act, and Louisiana’s Unfair Trade Practices and Consumer Protection Law.

In a statement, First Guaranty Bank denies such allegations, calling them “completely unfounded and frivolous”, adding that it “has not and does not engage in discriminatory practices”.

According to the lawsuit, the bank also required excessive collateral and unnecessarily supervised June’s farm spending account. The suit alleges that the bank forced him to reduce his sugarcane acreage against expert recommendations from Louisiana State University agronomists. First Guaranty Bank disputes this, arguing that “future loans to Provost were declined since his yields were too low to service the debt, and he defaulted on the prior loans”.

The lawsuit also alleges that the bank unfairly delayed the approval and disbursement of loan funds for farm expenses, and vastly underfunded June’s annual crop loans, which impinged on his ability to produce a good crop.

In 2008, June’s second season farming on his own, the sugarcane production cost was $615 per acre. But June was only loaned $194 per acre. After weeding and fertilizing, he had little left to repair or purchase equipment. By fall, he could barely afford to pay his workers, let alone plant new cane for future production.

The Provosts argue that First Guaranty Bank and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved years of unfeasible loans that were too small for the scale of June’s production and dispersed too late in the season – and that when he failed, they collected on his collateral.

Such lending discrimination, Angie argues, can be observed just by looking at the fields around south Louisiana. By summer, white farmers’ fields are well-drained, weed-free, laser-leveled, whereas black farmers’ fields are overrun with Johnsongrass, a noxious weed – visual proof, says Angie, that black farmers are provided fewer resources than white farmers.

“You have to see it as a giant web, and every time you move in one way, it pulls you back in another,” says Hank Sanders, an attorney who is regularly involved in strategy with the Provosts’ legal team. “White supremacy is such a powerful thing … and it manifests itself in these various entities and institutions.”

Now almost 76, Sanders was one of the primary lawyers for the plaintiffs in Pigford v Glickman, a groundbreaking lawsuit brought in 1997 against the USDA by black farmers alleging racial discrimination in federal farm assistance and lending. The Pigford case resulted in more than 15,000 claimants receiving compensation, including June, his brothers and Wenceslaus Sr. After Pigford, the 2008 farm bill and a 2010 vote by Congress led to the appropriation of $1.25bn for a settlement that included thousands of additional black farmers.

The Pigford case illuminated the long, old wound of black farmland loss in America, which began with a broken promise by the federal government to give 40 acres and a mule to each family of emancipated slaves. While Abraham Lincoln envisioned the USDA as the “people’s department”, black farmers have another name for the agency: “the last plantation”.

“The tactics are to strangle the life from all the black farmers, and it’s being done in multiple ways,” says Sanders. “And the US government is as much in on the strangling as any other entity … and has generally been complicit in running hundreds of thousands of black folks off the farm, and destroying their way of life.”

When June couldn’t afford labor, he worked long days alone. His mother, Bernadette, says he did “the work of four and five men”. He’d pick up tractor tires or 50-gallon drums by himself and shovel drains by hand. He’d go to work at 3am just to get everything done.

“There was always, ‘Mom, I don’t have enough money to do this,’” Bernadette says. “‘Look how long they’re taking with my loan. What am I going to do?’” Her voice breaks, and she begins to cry. “It seeped the life out of his body.”

“Give up,” she told him.

“Mama, I can’t, it’s my life.”

But there was another reason June could not give up. “He was forced by [another] bank to guarantee his parent’s loans,” says Angie, recalling that MidSouth Bank required June and his brothers to sign a security agreement for their father’s crop loans. Without his signature, June knew his father’s crop loan would have been denied, so he signed. “You can’t abandon your debt, because you can’t abandon your parents,” she says.

Robinson says the accumulation of generational debt highlights a discrepancy between lender treatment of white and black farmers. “If you look at the white farming community’s farm transition from one generation to the next, it’s smooth. If you look at black farm transition from one generation to the next, it’s chaos. They took [June’s] father’s debt and piled it on top of him. There’s no way [June] could have survived.”

In the lawsuit, lawyers for the family argue that First Guaranty Bank required far more collateral from the Provosts than similarly situated white farmers (an allegation the bank vehemently denies). The bank took lien positions on June’s personal residence, parents’ residence, farm equipment, farm payments from USDA, crops and the earnings from those crops, and equipment lease payments.

In his years of representing black farmers, Sanders says he’s seen clear patterns used by government and private entities to disrupt their farming operations. “If you rob somebody on the street, that’s a crime that carries a prison term. But in this web, if you make a decision with your pencil and your paper, it’s robbery nonetheless.”

In 2008, June struggled to make his crop loan stretch. He relied on old equipment that often needed to be repaired and couldn’t afford enough laborers to plant seed cane until November, three months later than guidelines which note a drastically smaller crop if not planted by the end of August.

On 8 November, while chopping the ground for new cane, June could barely stay ahead of the planting crew with a single tractor, so his father came to help.

“We can chop together,” Wenceslaus Sr told his son.

That evening, they left the field in separate vehicles, Wenceslaus Sr a few minutes ahead. But when June started down Highway 90, he saw cars pulling over, the glow of taillights, a cloud of dust. Wenceslaus Sr had flipped his truck. By the time Angie arrived, June was holding his father in the middle of the road. She remembers that it was chilly and damp, that milling season had begun, that the air smelled like syrup.

Wenceslaus Sr died in a single-car accident from a suspected heart attack. He was 66; he had endured two heart surgeries, diabetes, as well as a lifetime of hardships and discrimination.

His grave is decorated with silk flowers, and the headstone is etched with a tractor and stalks of sugarcane. The cemetery lies in clear view of MA Patout & Son sugar mill, which describes itself on its website as “the oldest family-owned and operated complete sugar mill in the United States”.

Before it became MA Patout & Son, the Patout ancestors operated a sugar plantation.

“A plantation was a factory, an industry that used enslaved people to make a product to make a profit,” says a tour guide for the Whitney Plantation, now a slavery museum, located in a nearby parish. “People said there was brutality in cotton, but death in cane.”

Built on the backs of slaves, the sugarcane industry buoyed the country’s early economy. Enslaved blacks were considered moveable real estate that could be mortgaged and sold. Men were referred to as “bucks”, women as “breeders”, and babies as “increase”. When sold, families were often separated. The forced labor of hand-cutting, grinding, and boiling cane was excruciating and dangerous. And there were brutal punishments, including execution.

In antebellum Louisiana, as the Patouts grew their plantation, they also grew their slave holdings. Simeon Patout was a “rather substantial slave owner for the time”, wrote Michael G Wade in Sugar Dynasty: MA Patout & Son, Ltd 1791-1993. Wade describes the buying and selling of slaves by Simeon and his wife Appoline – $1,600 paid for “Jenny and her four children, aged one to ten”; $3,000 cash paid for a family of six; $425 for 13-year-old Nancy.

By 1860, the Patouts owned 107 slaves.

More than a century later, the Patout family still owns the company, and, according to the website, elects board members “to fill the seats of their ancestors”. They also own three subsidiaries, including two other mills. The company reports a combined capacity for the three mills of 4.6m tons of cane per year.

In a separate lawsuit, the Provosts allege that in early 2015, MA Patout & Son breached a 2007 contract with June, which stipulated that June would mill his cane with MA Patout, and that MA Patout would harvest and mill the cane for an agreed-upon fee for a duration of 14 years.

(The mill declined to comment, citing the pending litigation with the Provosts.)

In the month before the mill was to close for the season, Randall Romero, CEO of MA Patout, sent a series of letters and emails to June, accusing him of hauling sugarcane to another mill – an allegation the Provosts deny. “In fact,” wrote Romero in a letter on 6 January, “we have pictures of your trucks delivering sugar cane to other factories”. He terminated June’s contract and offered a temporary agreement to finish the season, charging significantly more to harvest the crop.

June had two choices: sign what he considered to be a coercive contract and get his cane harvested – or refuse to sign, lose the crop, and fight back legally.

The family gathered to discuss June’s options. They all agreed: June should not sign. That decision meant leaving the cane to freeze in the field – a disgrace to any farm family and heartbreaking for June.

Frantically, he attempted to cut the cane himself and filed an emergency lawsuit against MA Patout. The mill acquiesced by cutting 300 acres of June’s cane, but it left between 300 and 400 acres untouched. By then, it had stood so long in the field that it was barely viable. June estimates a crop value loss of over half a million dollars. He says it was the final blow that forced him out of farming.

In a deposition on 28 November 2017, Romero stated that harvesting sugarcane just days before the closing of the mill – as was the case with June’s cane in 2015 – would be considered “impractical”, and would yield less sugar than if it were harvested earlier in the season. When asked if he agreed “that Provost Jr suffered damages as a result of MA Patout’s breach of contract”, Romero replied: “I’m sure he did.”

He also admitted to singling out June Provost for surveillance based on a rumor that he was hauling sugarcane to another mill. In a signed 2018 affidavit, the MA Patout & Son president, Jacques Hebert, submitted photographs of June’s trucks hauling sugarcane to Cajun Sugar Cooperative. The Provosts say it was Angie’s cane in the photos, not June’s, and that at the time she was farming independently of her husband as a separate legal business entity. In 2014, she had requested her own contract with MA Patout & Son, but had been denied, so she milled her sugarcane elsewhere.

A trial is set to begin in December.

Before June came three generations of sugarcane farm owners: his great-grandfather, the first in the family to own land; his grandfather, Frank, who bought 33 acres where the family built their houses; and his parents, who, as Angie says, “built a legacy” for their family by acquiring land and becoming skilled sugarcane producers.

Angie traces her ancestry to the coast of Cameroon, where her family members were stolen and sold as slaves to Louisiana’s sugar barons. Her great-great grandfather, Antoine, was enslaved at Oaklawn Manor, now the home of Louisiana’s former governor Mike Foster. Angie says it was winter when Antoine was freed, so he took “Winters” as his surname. He told his children that he spat on the ground as he left.

“You don’t understand discrimination and oppression unless you’ve lived through it,” says Robinson, an attorney for the Provosts. His own family once owned hundreds of acres across Georgia’s kaolin clay belt, but a company convinced his nearly illiterate grandfather to sign documents that he couldn’t read and bought the land for a fraction of its value.

“If you have not had dinner, supper, and lunch with oppression and poverty, then you might not want to fix it, because you can’t relate to it … but I don’t like looking at injustice and poverty and oppression, so I’m doing something about it.”

To look at June is to witness how heartbreak can change a face. You can still see the boy who wanted more than anything to farm, but now there is a bone sadness – dejection in his voice, a near-constant furrowing of his brow when he reflects on his lost land. “You see the depression in June’s eyes,” says Robinson, “And you see the fight in Angie.”

Indeed, Angie has become the family’s unofficial co-counsel, a fierce defender of the Provost legacy. She’ll hold court around the kitchen island for anyone who will listen – to the evidence they’ve pieced together, the binders of documents she’s compiled, every detail of the Provost story told with hairpin precision.

When Angie moved back to New Iberia as an adult, near where she was born, she says the place resembled a “good old boys’ club”.

There were different rules, racial segregation, and a corrupt hierarchy.

In 2014, the Iberia parish sheriff, Louis Ackal, made national headlines after a 22-year-old black man, Victor White III, died in the custody of sheriff’s deputies. Ackal claimed the young man shot himself, even as he was handcuffed with his hands behind his back in the back of a patrol car.

This “legacy of racial conspiracy”, which the New York Times described in a 2017 article about Ackal and New Iberia, is the backdrop for the Provosts’ allegations, and Robinson argues that modern day tactics used to set black farmers up to fail – such as the ones on display in the Pigford case – are the residue of Jim Crow.

Bryan Stevenson, the legendary Alabama lawyer and creator of the Memorial for Peace and Justice, a national lynching memorial, said on WNYC’s On the Media: “people weren’t lynched just because they were accused of some violent crime. They were lynched because they were successful in business. They were lynched because they insisted on being treated fairly. When they asked for better wages as sharecroppers, they would be lynched … this violence was intended to sustain racial hierarchy”.

It is not far-fetched, say the Provosts, that in a community so steeped in racism, in an industry that has long discriminated against black farmers, there could have been a concerted effort to remove June Provost from his land and livelihood.

On the night of 25 September, Angie sent an email to friends and family. “My soul is in despair as I write this letter to confirm the loss of our home via a sheriff sale scheduled for tomorrow @ 10:00am.”

The following morning, in the foreclosure sale, the Provosts’ home and surrounding acreage went to First Guaranty Bank, the sole bidder. June and Angie moved in next door with Bernadette, but her house is currently in foreclosure proceedings with MidSouth Bank.

Soon, they say, they could be homeless.

But Angie and June say they’ll continue to fight – to prove that the sale of their home was an illegal foreclosure based on years of discriminatory lending and fraud, to be reimbursed for damages, and ultimately to be able to farm again. They also want justice for other black sugarcane farmers and imagine the possibility of a class action lawsuit if others come forward.

They note challenges, including the lack of legal representation available in black rural communities, and the frightening nature of pursuing legal action against largely white businesses with plenty of resources.

“Our families are all divided. There are conflicts everywhere. These people bank on us staying divided,” says Angie. “Because if we actually came together and said what was really going on, there would be a revolution here.”

Nearly every night, the dreams come. Sometimes June is checking the fields with his dad, or he’s watching the cane yellow and freeze all over again. He’s begun grinding his teeth and calling out in his sleep. Angie dreams that people are chasing her, and she routinely wakes up in a panic. Or she dreams of the children they won’t have since deciding it’s not safe to start a family, given the threats.

Since the problems began with their land, Angie and June have experienced panic attacks, anemia, and chronic illness, and they see therapists for stress and depression. A couple of years ago, June was hospitalized for gastrointestinal bleeding. They keep a bag packed by the door in case they need to leave quickly, and they go everywhere together, even to the grocery store.

The May sky over the cemetery is blue as a bird’s egg, and the sugar mill spreads across the horizon – jutting smokestacks, bright yellow scaffolding, a long sweep of gray buildings that Angie says includes old slave quarters renovated into the MA Patout & Son offices. From inside the complex of the mill, a horn blows, long and low.

There is a sheen of sweat on June’s face as he walks quietly toward his father’s grave. He points to rows of stone mausoleums decorated with flowers. “These are all black sugarcane farmers,” he says, and shakes his head. “Every one of them passed too young.”

June stands at his father’s grave and weeps. “I miss him so much,” he says to Angie, “All he wanted was for his family to farm, his grandsons … it’s not fair how they did it. It’s not right.”

Angie reaches up to touch his face. “It’s not fair at all, but we fix what’s not fair,” she says gently. “Look how you’re shining a light on your dad’s story. He would be so proud of you.”

This story was supported by the Puffin Foundation and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project