While discriminatory practices in real estate were outlawed in 1968 with the passing of the Fair Housing Act, their shadow remains today. We can see it right here in Coronado.

Back in the early 1900s, Coronado was home to a thriving population of Black Americans who worked, owned homes and businesses, and lived alongside white residents in the community. In 1906, 12.5% of the Coronado High School graduates were Black, according to Kevin Ashley, local historian. Between the late 1880s and into the 1920s, Black Americans made up 2-3% of the Coronado population, far higher than the statewide average of 1%.

But by the 1960s, Coronado’s population of Black Americans had virtually disappeared, according to Ashley. By 2023, less than 0.6% of students in the Coronado Unified School District identify as African American.

What happened?

“What happened is a darker chapter in American history that occurred from the 1920s to the 1960s which involved racially restrictive practices in real estate,” said Ashley. “Coronado was not immune.”

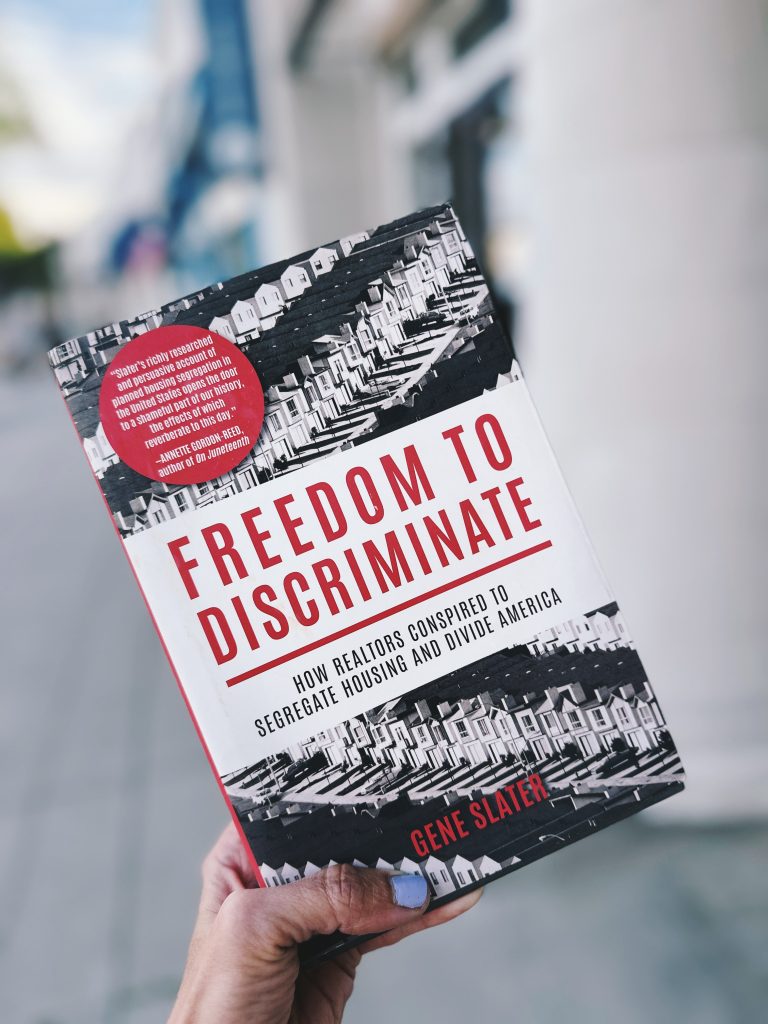

Author Gene Slater, an expert on these practices, spoke at a special event last month at the Coronado Historical Association (CHA) called “The California Innovation No One Talks About: How and Why the Real Estate Industry Segregated America.” The engagement ran in conjunction with CHA’s current exhibit, “An Island Looks Back: Uncovering Coronado’s Hidden African American History,” of which Ashley is guest curator. The exhibit is set to run until early June.

At the event, Ashley introduced housing expert Gene Slater, who wrote the book, Freedom to Discriminate: How Realtors Conspired to Segregate Housing and Divide America.

It’s a story of innovation and the building of barriers, and much of it started in California, according to Slater. While most neighborhoods were racially mixed in the early 1900s, real estate agents bought into the myth that selling homes to non-white buyers would greatly depreciate surrounding property values.

“Segregating neighborhoods became a new, 20th century invention,” said Slater.

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) actually made it part of their Code of Ethics in 1924. Article 34 days that a realtor must “never introduce into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to the property values of the neighborhood.”

And so real estate agents became racial gatekeepers. Not necessarily because they themselves were prejudiced, but because they believed they were doing the right thing for their clients, while following the strict rules laid out by the realtors.

“What happened in Coronado is identical to what happened in hundreds of other cities,” said Slater. “Real estate agents would sell homes, and say, ‘don’t worry, you’ll be protected against minorities,’ and homeowners associations and public officials looked to the realtors to protect the all-white areas.”

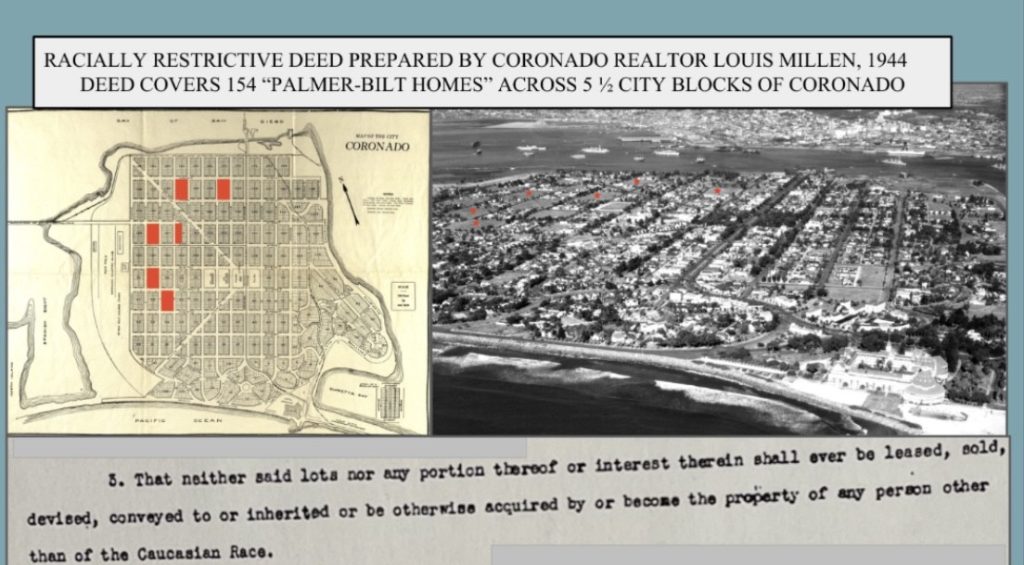

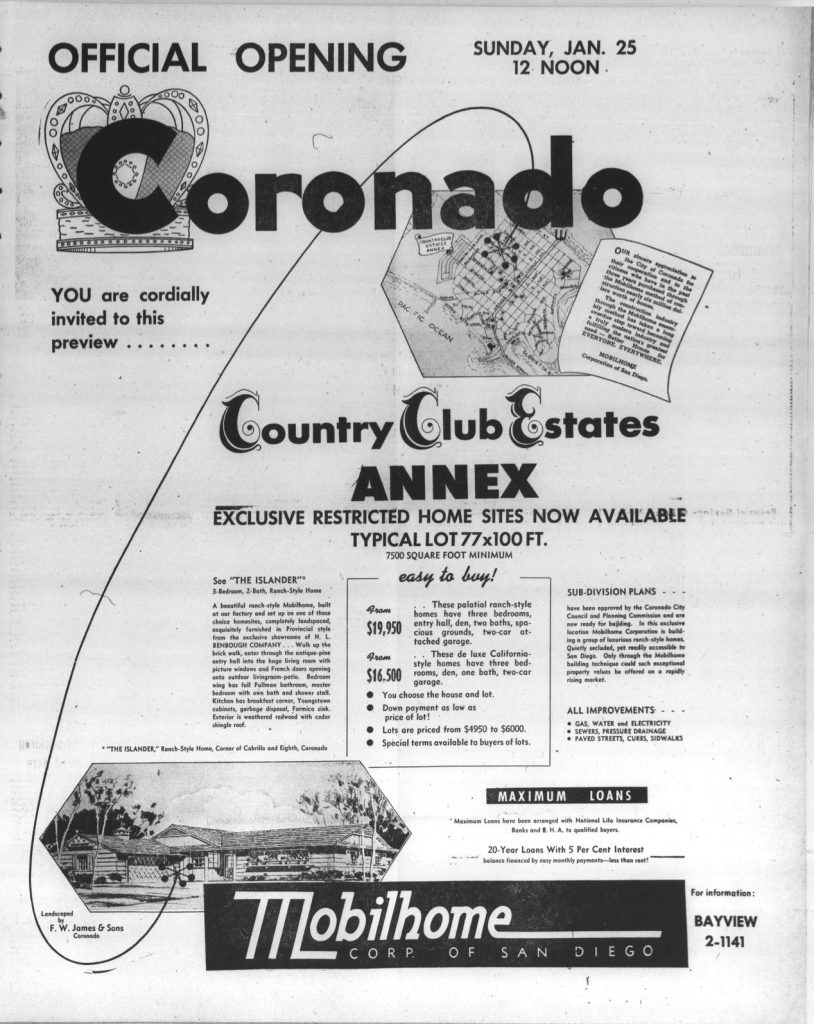

Exclusivity became a marketing tool, a way to sell more homes. We can see how this played out here in Coronado in the form of exclusionary covenants and restrictive deeds.

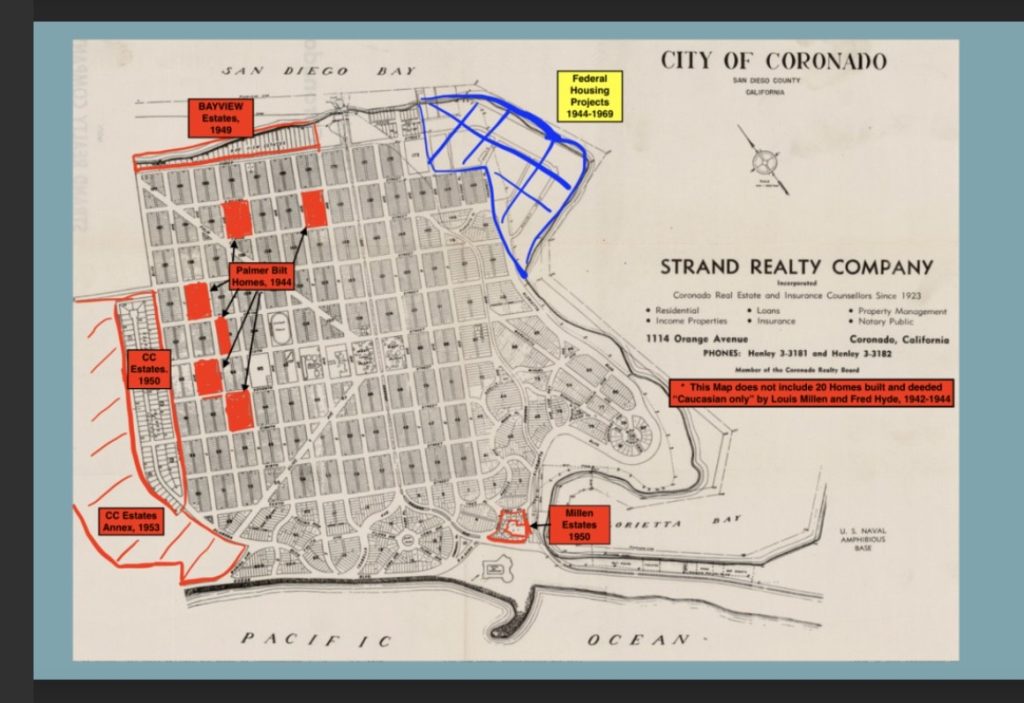

“In one day in 1944, a single restrictive deed was signed by Louis Millen, who was President of the Coronado Realty Board and a co-founder of the Coronado Historical Association, that took six city blocks and made them restricted to Caucasians only,” said Ashley. “Bay View Estates was also restricted to whites only. Every single one of those lots is Caucasian only. Same thing with Country Club Estates.”

Segregating neighborhoods was constructed by private business trade organizations and real estate practices to sell homes and maintain business practices, according to Slater.

“America in the 20th and 21st century becomes a story, not of barriers being reduced and by government fostering equality, but just the opposite,” said Slater. “Residential segregation and its legacy today isn’t peripheral to American history but at its core.”

When the Federal Housing Administration began offering loans with low down payments in 1934 to revive the housing industry, Black Americans were almost always left out. Out of 12 million homes financed with federal guarantees from the 1930s to the early 1960s, less than two percent were sold to minorities. The numbers were equally dismal for VA loans.

This racial system was so effective that by the 1960s, Black Americans were excluded from buying 98% of new homes constructed and excluded from 95% of all neighborhoods, according to Slater.

“Looked at as a whole, FHA was among the most effective machines ever created for generating wealth,” wrote Slater.

But non-white buyers were left in the dust. This includes Black Americans who returned from fighting in World War II, only to find themselves locked out of the housing market while their White counterparts bought homes.

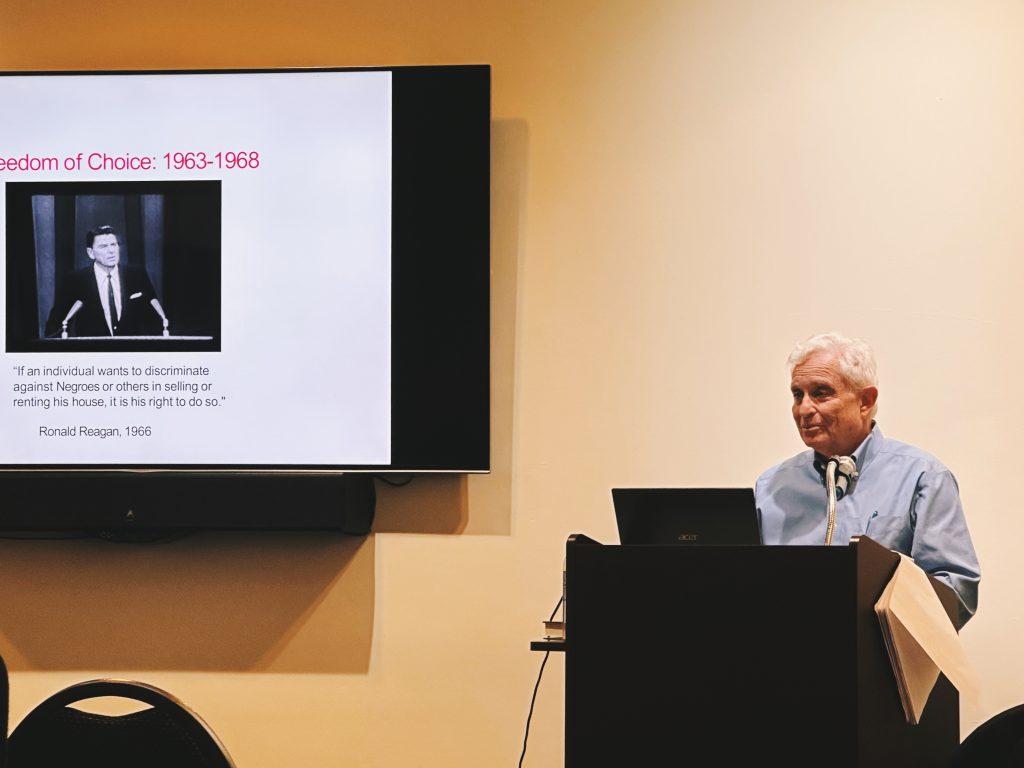

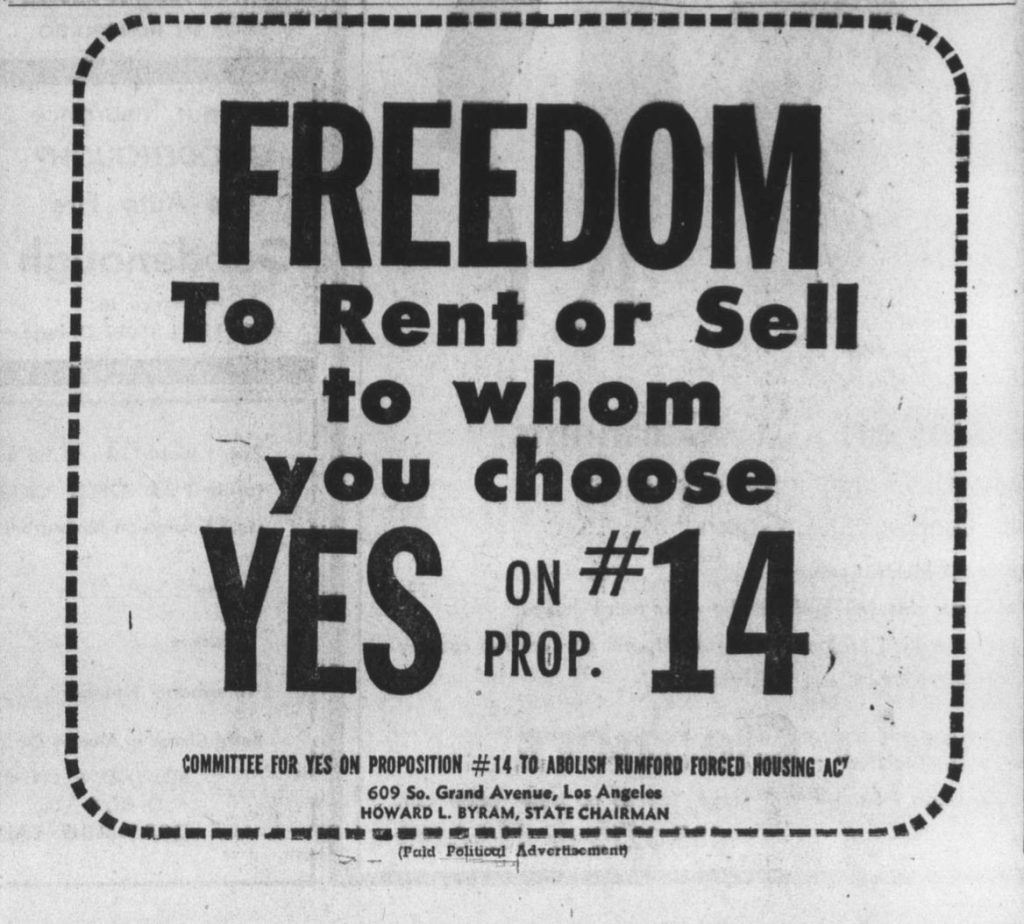

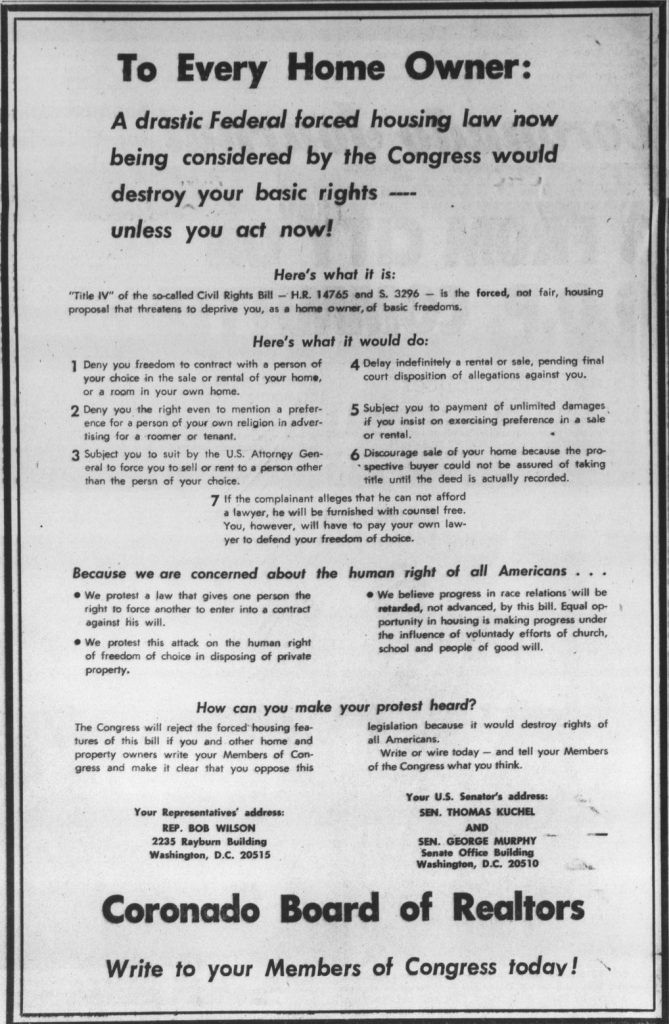

And it gets worse. Despite new legislation like the Rumford Act in 1963 designed to curb discriminatory practices in real estate, California went the opposite direction. The California Real Estate Association (CREA) funded and promoted the ballot initiative Proposition 14, which if passed would become an amendment to California’s Constitution which was explicitly designed to prohibit all fair housing laws and regulations in California, while making it legal to discriminate against buyers.

CREA argued that Prop 14 was a vote for freedom—the freedom to decide who you would sell your home to. Freedom meant the ability to say that no, you didn’t want to sell to a person of color. The organization called the federal anti-discrimination laws “drastic” and “forced” that they threaten to “deprive you, the homeowner, of basic freedoms.”

Anti-discrimination laws were a threat to human rights, said the realtors, effectively arguing that property rights were equal to human rights

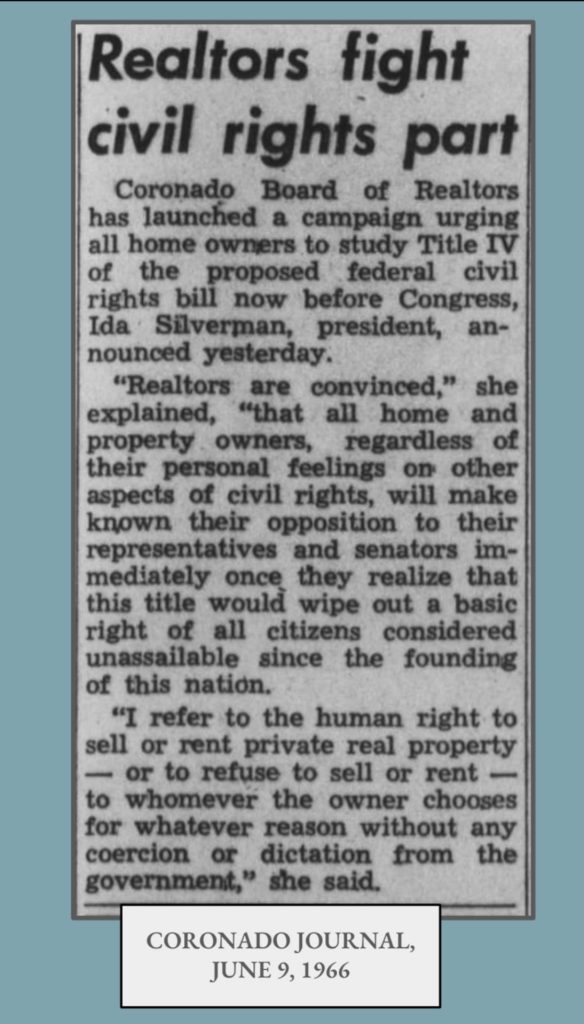

The arguments worked. Prop 14 passed at a rate of 2-to-1 across the state, and 3-to-1 in Coronado. While it was deemed unconstitutional and overturned in 1966, the Coronado Realty Board continued to oppose Federal anti-discrimination laws for several years.

“It’s the idea that your rights include the rights to control your environment, who can live around you, what kind of house they live in and what they can do,” said Slater. “That idea is at the heart of what the realtors did, and very much at the heart of Coronado itself.”

Then Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The Federal Fair Housing Act was signed into law just seven days later, which expanded on previous acts and prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin and sex.

But according to Slater, some racially restrictive real estate practices continued, just in less obvious ways.

“It’s driven by informal discrimination, by appraisers, by brokers, by banks turning down Black people at twice the rate as White people with the same income and credit scores,” said Slater. “So, you have a whole series of things that are happening that are compounded by this legacy in the form of limits on household wealth.”

This legacy is seen in Coronado today, in the city’s demographics and homogeneity, said Slater.

“Without the racially restrictive exclusivity, Coronado would be a very different environment,” said Slater. “You would see more diversity of people, more diversity of home types and more diversity of income.”

It all centers on the idea of just who is entitled to American freedom. In the eyes of the realtors, freedom belonged to each person separately as a possession, so that freedom for others diminished one’s own, according to Slater.

“I think people look at [racially restrictive real estate practices] and think, well, that’s the past. And it was all cured by Fair Housing, wasn’t it?” said Slater. “In general, as a country, we are kind of blind to how things — that we now take for granted — came to be.”

Although the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, it wasn’t until 1989 that Frank and Alice Fried became the first documented Black Americans to buy a home in the village, according to Ashley.

“This shows you the gravity of the situation in Coronado and why in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s there was really no Black community left,” said Ashley “By the time African Americans gained access to the Coronado Real Estate market, the Black middle class had been priced out of the market. This story was repeated in towns and cities across America, and is the greatest single contributor to the disparity in household wealth between Black and White Americans.”

In 2020, the National Association of Realtors apologized for its role in housing discrimination. and vowed to keep working to correct lasting inequities in housing.

In 2022, the California Association of Realtors issued its own apology for endorsing racial zoning, redlining and racially restrictive covenants.

CHA’s current exhibit, “An Island Looks Back: Uncovering Coronado’s Hidden African American History,” is set to run until early June at the Coronado Historical Association & Coronado Museum at 1100 Orange Avenue.